The Silver Treasure of Rajasthan

by Stuart Freedman, Fire Mountain Gems and Beads®

Chris and I had just finished a romantic dinner in San Francisco, a candle-lit affair of Alaskan king crab and spinach Florentine with a nice bottle of Chardonnay. As we strolled arm in arm down Powell Street, our attention was caught by the glittering of faceted gemstones in the window of a small mom-and-pop jewelry store.

The shop was closed, but several simple pieces were spotlighted. We both glanced rapidly past the jade brooch and the crystal earrings and were startled to find, off to the side, a stunningly elegant lapis lazuli necklace. It was made of round beads of Afghanistan's finest royal blue stone— interspersed with something extraordinary. Linking the lapis lazuli beads were ornate silver beads unlike any we'd ever seen. Perfectly spherical silver mini beadlets textured the beads in exquisite patterns. T he art and craftsmanship rivaled examples of the prized and difficult granulation technique from Bali, Indonesia.

With a squeeze on my arm, Chris said in a barely contained whisper, ''Stuart, I love that necklace.''

The following day, we were waiting for the lovely shopkeeper from Hawaii when she opened her doors. We introduced ourselves and asked about the origin of the silver-beaded necklace. The woman told us that she had bought the necklace from a man from India. The unnamed man dropped by her shop every couple of years. She knew one thing only about him— he was from Rajasthan. We paid for the lapis lazuli and silver art piece and then profusely thanked the shopkeeper for the information.

Chris and I built this business out of a love for beautiful beads and the desire to create a fantastic selection for our customers. We'd already made discovery trips that year to Thailand, China and Russia, but now we knew that we had to mount an immediate expedition to India.

For this Gem and Bead Team mission, I tapped Sukhdev Singh Nagi, our staff gemologist. Sukhdev is a Sikh originally from New Delhi, India. He speaks Hindi, Punjabi and English and reads some Sanskrit. He was the perfect companion for the journey.

Traveling halfway around the world by air, our route from Oregon took us through Seattle, then Hong Kong before finally arriving in New Delhi. From New Delhi, we'd make our way southwest into Rajasthan, the Land of the Kings.

Despite British rule of India from the 1700s to the 1900s, India remains a mystery to the West. Its name conjures images of dusty Hindu sadhus with matted hair and beards, Buddhist monks draped in saffron robes, gurus, snake charmers, jeweled maharajas, bearded Sikh warriors and fabulously carved Jain temples. And we've seen photos of elephants, tigers and camels in environments ranging from the jungle to the desert. But beyond these fragmentary glimpses, stepping into the dazzling color of the real India is intoxicating— and disorienting.

We weren't ready for what happened just after landing in New Delhi. As we unbuckled to collect our carry-ons, the Indian flight attendant sprayed us with a harsh metallic-smelling chemical. Then, still trying to overcome the strong scent of the disinfectant, we were blasted by the throat-parching air of a 110° sun-drenched afternoon. Between the terminal and the car rentals, our senses were overwhelmed. India's population has now risen to over one billion people, and it seemed to me that they were all in New Delhi. The local custom, and indeed the only practical approach, is to barge your way into line through the tightly packed humanity. From that proximity in the searing heat, the aroma of spices and curry mixed with the pervasive scent of perspiring bodies was close to overwhelming. We were relieved to finally be out of the crowds and on our way in our rented SUV until we discovered that this was to be an all-windows-down trip. As luck would have it, the air conditioner was on the blink.

We drove on the left side of the road (a result of British rule until Indian independence in 1947) about 160 miles southwest to Jaipur, crossing a vast plain of wheat, millet and cauliflower fields. Along the way, we saw both modern and archaic modes of transportation: buses, SUVs and motor scooters alongside camels, elephants and oxen. Up ahead, we spotted an ill-defined rouge tint on the western horizon. Making our approach to the foothills of the Aravalli Range, we were suddenly hit by a howling sandstorm. The windows went up, and we inched our way along for the next hour in our SUV oven.

By the late afternoon, the skies had cleared, the temperature had dropped a few degrees to simmer instead of boil, and we found ourselves entering the main northeast Zorawar Singh Gate of Jaipur. As we passed through the old city's 20-foot-high wall, we were startled by the color of our surroundings. The entire city is painted in pinks and reds with bright white accents. Since the 1800s, it has been called the Pink City.

Our senses were assaulted by the cacophony of sounds, sights and smells: the dense crowds; flowing saris and mirrored skirts; women's bright, chunky gold and silver jewelry; the ever-present forehead tika and bindi marks; the densely traveled streets lined with vendors of fruits, flowers and spices; the enticing aromas of battered and deep-fried pakora vegetables; mouth-watering marinated goat and chicken kebabs cooked in tandoori clay ovens; sweet gulab jamuns and fried pastry samosas . Images of the new clashed with the old. Trotting down the street was a camel pulling a wooden cart— which was rolling on Firestone tires. And the magical Hawa Mahal, the Palace of the Winds, loomed overhead with its intricately latticed screens and arches.

The country is steeped in the images, lore and rituals of ancient religions and cultures. One of the religions, Hinduism, has origins that can be traced to the Indus Valley civilization, which flourished nearly 5,000 years ago. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Islamic invaders conquered the Rajput warrior clans of Rajasthan and northern India. Today, out of a Rajasthani population of 68 million, 89% are Hindu, 9% are Muslim and about 1.3% are Sikh.

We knew that some of the subcontinent's finest art forms are found in the state of Rajasthan. It's not surprising. The travails of living in these harsh lands— with an unforgiving dry season of sandstorms alternating with months of pelting monsoon— have inspired both the use of kaleidoscopic color and the finest artistry. Beyond beautiful Kundankari inlaid gemstone jewelry, Rajasthan artists produce exemplary kagzi pottery, epic phad paintings, lehariya tie -dye textiles and Meenakari enameling.

Since antiquity, the Indian subcontinent has been known for its wealth in precious gemstones: diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds. Jaipur is now a lapidary center, specializing in the cutting of emeralds and diamonds from Africa, South America and other parts of India. While precious metals have always been an integral part of Indian jewelry, silver has special significance in these desert lands of Rajasthan. According to Hindu Ayurvedic herbal medicine, silver is cool and therefore good in hot climates— and it came to be understood that it can lower high blood pressure. Silver and ivory ornaments and jewelry are found everywhere in Rajasthan.

The ornate sculpting of silver and gold has come into its own since the trade in ivory ended in 1989 . Many of the highly skilled ivory carvers moved to the medium of precious metals, using skills influenced by the art of Bali, Indonesia. Rajasthan is now known for its superior bead silversmiths.

We were searching for genuine treasure. Our quest was for the fine sterling silver granulated beads made there. I felt the emblem of our journey in my pocket, the cool solidity of Chris' silver and lapis lazuli necklace.

Traveling south into the new part of the city on Moti Dungri Road, we found our lodging in a hotel converted from a past maharaja's estate.

The following morning, Sukhdev and I started exploring the network of silver contacts in Jaipur. The hotel's concierge had overheard our conversation about silver beads in the lobby and had enthusiastically suggested we talk to his brother-in-law, who he said traded in fine silver jewelry. We made our way on dusty streets by motorized rickshaw to what was literally a shed with peeling rust-brown paint. The brother-in-law was indeed a silver merchant, but Sukhdev found his silver of poor quality. We were also none too pleased to find a dirty workshop and two 11- or 12-year-old apprentices. We knew that a young person must be 14 to work legally in India.

Stopping by a series of shops, each with standard-sized storefronts and signage, we found average-to-good silver beadwork, but no evidence of the fine workmanship we were seeking. We were pleasantly stunned to learn, however, that many of the gemstone and bead dealers we met were familiar with the name and reputation of Fire Mountain Gems and Beads. They were all eager to do business with a company that was literally on the other side of the earth.

On Shiv Road, I noticed a red-shirted, heavily mustached Indian man of about forty who seemed to be shadowing us from shop to shop. Sure enough, inside the next shop, he made his move. Just as I was showing my prized lapis lazuli and silver necklace to the shop's owner, the man suddenly withdrew several average pieces of silver jewelry from under his red shirt and threw them on the counter with our piece. With fast-spoken British-accented English, the man proceeded to set up his own version of the “shell game,” obviously planning to make away with our prized jewelry.

I called Sukhdev in from the storefront, and he quickly took measure of the situation— as well as the combative nature of the intruder. As the mustached man reached to his side for what might have been either a dagger or a gun, Sukhdev strode directly up to him and spoke to him calmly but firmly in staccato Punjabi. The man seemed to recognize Sukhdev as a Sikh of warrior repute, showed wide eyes of panic and skittered out the shop's door. In a full run, he crashed through a display of brass wares before disappearing into the crowd.

After the incident, we collected ourselves and recovered while sipping chai and munching on samosas from a roadside vendor. What my companion told the would-be thief will forever remain a mystery. When I asked him what he said, Sukhdev's only response was a confident smile.

This was to be our last day in Jaipur, and we were both dejected over our failure to discover the source of the silver beads. At dinner I found myself rolling the beads of Chris' necklace between my fingers, treating them with the reverence of prayer beads. Our gracious young waitress glanced at my hands while taking our order, and her face suddenly lit up in a glorious smile.

Rapidly speaking to Sukhdev in Hindi, I recognized the phrase for “I know.” Parting her robed top at the neckline, she revealed a simple leather thong on which hung three beautifully patterned silver beads. With soaring spirits, Sukhdev told me we had reached our goal! The girl knew the dealer of the beads and would take us there tomorrow.

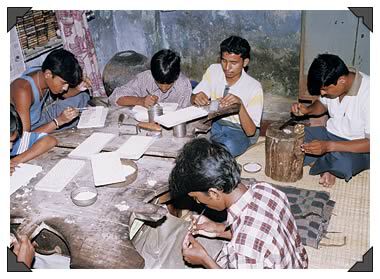

There was no question now that we’d extend our stay in the glorious state of Rajasthan. The next day we were escorted to the top floor of a stately two-story pink building in the old city— zand met the turbaned merchant who represented the source of the fine-finished Rajasthani silver beads. First, Sukhdev quickly determined, by using his portable silver testing kit, that the silver used was indeed 92.5% silver, the mark of sterling. Second, he determined that these beads were the same quality as those in my pocket. They had the same precise craftsmanship , the unique patterns and the refined state of polish. There was little doubt that the beads from Chris' necklace had come from this shop.

We took two days reviewing the dealer's unique designs and visiting with his master artisans. The proof was in the work. Each entirely hand-crafted bead was a work of artistry and precision. The time-honored custom of negotiation took place on the third day and extended until late in the evening. The deal was finally sealed with a handshake, and in this place, a man's word is his honor.

Our Rajasthani host presented us with a feast to seal our friendship. Our appetizer was papadums, delicate crispy crushed-lentil wafers with a peppery aftertaste, served with a green hot sauce of peppers and cilantro and another of sweet apple-buttery tamarind. Then came naan , a wonderful puffy flatbread made of milk and yogurt spread with ghee and poppy seeds. It was like biting into a cloud! Dahl makhani, a mildly sweet lentil soup with a split pea soup texture, came with the naan.

Tandoori oven-roasted lamb arrived on a sizzling bed of onions and peppers— to be drenched in a spicy-sweet creamy garam masala sauce, rich with yogurt, coconut milk and cashew. Two fairly neutral dishes arrived to soothe the spicy heat: delicate saffron basmati rice and a cool cucumber-yogurt sauce. The finale completed the range of tastes. First came a cool, thin rice pudding called kheer sprinkled with cinnamon and crushed green pistachio, and then came the spectacular mawa. The mawa was the master's finishing touch: a crisp, chewy Indian-style candy made from full-cream milk and sugar sprinkled with nasturtium flowers and garnished with varq, a very real silver foil. Surely, we were in the Land of the Kings!

With great warmth, our host thanked us for our friendship and explained that the order Fire Mountain had placed would employ over two hundred silversmiths at a monthly salary twice the government-set minimum wage. This represents a huge boon to these workers and their families. Now they can better afford food, shelter, medicine and the all-important education for their children. This was a significant boost to their local economy, as Rajasthan has one of the highest unemployment rates in all of India.

Poverty and illiteracy are the two most pressing problems for Rajasthanis. Chris, Sukhdev and I were gratified to be able to make a dent on both fronts. One of the compelling purposes of Fire Mountain Gems is to help people find satisfaction and self-reliance through the power of work and by developing their skills to their highest potential. We've seen this transform peoples' lives at home through our contracts with Goodwill workers, and we're seeing it happen now in foreign lands like Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.

The Hindus believe that we will all go through a series of reincarnations, leading us eventually to the spiritual salvation of moksha. Accumulating good karma speeds us to our release from the cycle of rebirths.

Perhaps by helping some of these Rajasthani artisans to be more productive and self-sustaining, we'll add something to our “karmic accounts.” Maybe we can help make this world a better place, one bead at a time.

Love, Stuart, Chris and Sukhdev

*Note: Since the writing of this article, Stuart has sadly passed away. However, his enduring story, impactful work and visionary spirit continue to thrive within the legacy of Fire Mountain Gems and Beads.

Have a question regarding this article? Email Customer Service.

Copyright Permissions

All works of authorship (articles, videos, tutorials and other creative works) are from the Fire Mountain Gems and Beads® Collection, and permission to copy is granted for non-commercial educational purposes only. All other reproduction requires written permission. For more information, please email copyrightpermission@firemtn.com.