All About Gemstones

Gemstones are a rich and complex topic, beyond their surface appeal of color and shape.

They are found all over the world, beginning as minerals, rocks and organic formations that are desired for their specific colors, phenomenon, shine, inclusions or rarity. Not all gemstones are appropriate for all applications, so knowing the characteristics of different gemstones means better design decisions. Any jewelry maker who gains a working knowledge of certain gemological terms can create designs that fully unlock a gemstone's potential.

What do interested jewelry makers need to know? Some terms to be aware of are:

Natural vs Treated vs Synthetic vs Man-Made vs Imitation

The jewelry-making industry identifies gemstones in the following categories: natural, treated, synthetic, man-made and imitation. Understanding how gemstones are created allows jewelry makers to be more confident when shopping for beads and components, and then turn around to better explain their value to customers. When given the same cut and polish, generally a quick glance won't be enough to distinguish if a gemstone is natural, treated, synthetic, man-made or imitation. Which is why, by law, anyone selling any gemstone material must disclose its nature. Since most of us don't have a personal gemologist on hand, here are some explanations designers may find helpful:

Natural gemstones come from the purest source—nature. They can be inorganic (emerald, larimar, opal) or organic (amber, coral, pearl). They are created over a long period of time without the aid of humans. Natural gemstones can be found deep within the earth, along riverbeds, lining rocky cliffs and even from space. By the time they're sold, natural gemstones have been cut or polished, but not enhanced or altered in other ways.

Examples: fluorite, labradorite, crystal quartz, peridot, tourmaline

Treated gemstones are natural stones that have been enhanced to improve them in some way that’s desirable to customers. Usually, this is enhancing phenomena, color or clarity. There are a variety of treatments and enhancements used to improve natural gemstones, including heating, oiling, coating and more. Some jewelry makers view treated gemstones as synthetic or created, but the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) simply lists them as enhancements to natural gemstones. See AGTA’s Gemstone Treatment Guide for full descriptions and definitions.

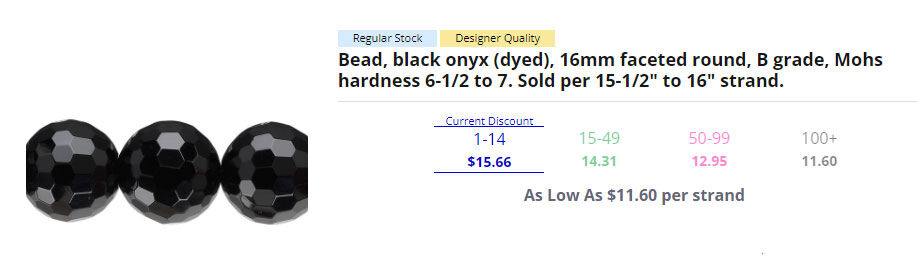

Examples: emerald, turquoise, citrine, black onyx, topaz

Synthetic gemstones have all the visual, chemical and physical properties of their natural counterparts, but they are created in a laboratory. Many other terms are used interchangeably with synthetic, such as "created gemstones," "artificial," "lab-grown," "lab-made," etc. Scientists use the same elements and conditions found in the earth to create a synthetic version of the natural gemstone, but in a much shorter time using modern technology and equipment.

Natural gemstones are created in nature, so they will often have minor flaws, imperfections or inclusions. Synthetic gemstones usually appear flawless, giving them added appeal for those wanting perfection. With their immaculate beauty and matching chemical makeup, the distinction is more appropriately labeled as synthetic. They are not "fake" gemstones—they are simply manufactured by people instead of nature.

Man-Made gemstones are often labeled interchangeably with Synthetic or Imitation gemstones, depending on the material that’s been created. An important distinction between synthetic gems and man-made gemstones is that a synthetic gem contains the exact chemical composition as its natural counterpart, whereas man-made gems may not.

Examples: Gilson® opal, goldstone, Hemalyke™

Imitation gemstones are also referred to as Simulated. These gemstones do their best to look like the real McCoy, but are manufactured from glass, plastic, ceramic or other materials. These gemstones do not have the same chemical properties as their natural counterparts. Many do such a fine job mimicking natural gems that it can sometimes be difficult to spot the difference without a closer look.

Examples: cubic zirconia, crystal- or glass-based pearls, "turquoise," "malachite"

As with most products in the marketplace, supply and demand causes prices to change and fluctuate. Since natural (and treated) gemstones come from limited resources, some are considered rare and may garner a heftier price tag. Synthetic and man-made gemstones are generally lower in price but aren't always inexpensive due to their fabrication process. Imitation gemstones are often the most affordable and—like synthetic—they can be great alternatives to natural gemstones.

Deposits and Other Sources

Every natural and treated gemstone comes from somewhere. Depending on whether it is organic or inorganic, a gemstone material can be made by a living creature, found deep within a planet, lying on its surface or floating in outer space. A majority of gemstones are inorganic: minerals, rocks and natural glasses which are found in deposits or strewn fields.

Deposits are sources for mineral, rock or volcanic glass gemstones. There are both primary deposits and secondary deposits for gemstone materials. Primary deposits are located directly at the site where the gemstone was formed, while secondary deposits are sites to which the gemstone has been moved. Diamonds, lapis lazuli and obsidian (a volcanic glass) are all mined from deposits.

Secondary deposits (sometimes called "placers") are often created by the movement of wind or water, which release gemstones from their original location and carry them downwind or downstream. Riverbeds are a common secondary deposit for gemstone materials around the world. Secondary deposits Baltic amber and Whitby jet can be found on beaches, where deposits of the gemstones run under the sea floor and are eroded from the host material by the water.

In developing nations, mining for gemstones is a labor-intensive job for the human body. These miners work in open pits with makeshift tunnels dug alongside gemstone deposits where they use hand tools to remove gemstones from the surrounding earth and rock. In places run by major corporations with deep pockets, deposits are mined underground using industrial excavators, hydraulic drills, underground vehicles and "shaker" machines which separate rocks into various sizes. Mining efforts for secondary deposits in riverbeds or seashores are essentially larger productions of traditional techniques used for gold-mining such as sifting and panning.

Strewn fields are areas where meteorites and/or ejecta from their craters are dispersed. Natural glasses such as moldavite and tektite—as well as carbanado diamonds, olivine and moissanite—are found in strewn fields, either from a meteorite's mid-air fragmentation or from fragmentation upon impact. There are laws surrounding the collection of meteorites and other ejecta from strewn fields, so check your national and local regulations or buy from reputable dealers.

Gemstones—and gemstone grades of particular minerals and rocks—are a finite resource. Larger deposits of some gemstones are being "worked out." In other words, many of the better grades of gemstones such as malachite, agate, garnet and carnelian are becoming harder to find as their deposits are mined. Though there are still gemstones left, a lot of the material will eventually be lower-grade quality or require more intensive mining techniques or locations to access.

In addition, some gemstones are becoming harder to acquire due to safety regulations and governmental control (such as amber, cultured pearls and turquoise mining in China). Fortunately, these protocols now provide safer working conditions for miners and also help control the environmental impact of mining.

Depending on the amount of a certain type of gemstone that can be uncovered (and the areas in the world where it can be found), a gemstone can be described as rare as well as beautiful. Certain parts of the world are known for the types of gemstones discovered there:

- Australia: Opal

- Africa: Diamond

- Sri Lanka: Sapphire, Ruby and many more

- Brazil: Amethyst, Emerald, Citrine and more

- Columbia: Emerald

- Arizona, United States: Sleeping Beauty Turquoise

- Tanzania: The only known deposits of Tanzanite

- Dominican Republic: Exclusive deposits of Larimar

- Alberta, Canada: Ammolite

Eventually, many gemstone deposits could be depleted; yet there could also be new gems unveiled. Some popular gemstones were only discovered in the latter half of the 20th century, including tsavorite (1961), tanzanite (1967), larimar (1974) and chrome diopside (1988)! And don't forget, there are tons of finished gemstones already out there in the world waiting to be passed on to new generations as heirlooms or to be sold to new owners and turned into magnificent new pieces of jewelry.

Mohs Hardness

Hardness can be described as a gemstone's resistance to being scratched—or conversely, its ability to scratch other things.

The scale used to measure a stone's hardness is called the Mohs Hardness Scale, and it runs from 1 to 10. A human fingernail is about a 2-1/2, a dime is 3-1/2 and window or bottle glass is a 6.

One popular scene in movies or TV shows is where a person scratches glass using a diamond. Diamond, at 10 on the Mohs scale, is the gold standard of hardness. It is extremely resistant to scratching, and can scratch most other things. This hardness is why low-grade diamonds are used so often for industrial applications like sanding, drilling and cutting—and high-grade diamonds are an ideal stone for designs that need to withstand a lifetime of wear and tear, such as a wedding ring.

On the other end of the Mohs scale is talc. Talc is so soft that it won't scratch anything. Because of its low Mohs score, talc probably wouldn't be used in any jewelry application. It is much more common to see talc in its powdered form, which is used in wood-working and glazing of ceramics.

The Mohs hardness of gemstone materials is included in individual product descriptions on the Fire Mountain Gems and Beads website:

Knowing a gemstone's hardness helps designers determine which forms of jewelry it is appropriate for. Rainbow fluorite, with a Mohs hardness of 4, might not be the best choice for a bracelet or ring, while being a grand option for earrings and necklaces. On the other hand, garnet's 7 to 7-1/2 hardness makes it an ideal choice bracelets and rings.

Optical Phenomena

Optical phenomena are the way gemstones interact with a light source—the reflection, diffraction, absorption and/or diffusion of light. These include color, interference and inclusions.

Color exists in gemstones due to which waves of light exit the stone and which are reflected back. Many stones are idiochromatic ("self-colored"), such as ruby or peridot, due to the chemical makeup of the crystalline structure at the molecular level.

Other gemstones are pleochroic ("more-colored"), such as iolite or natural tanzanite. Pleochroism refers to gemstones showing different colors based on the angle of view. This comes from how light polarizes inside the crystal structure, much like "blue blocker" sunglasses work to reduce glare.

Some gemstone colors change depending on what type of light source they are viewed under. This color change is starkly obvious, so all gemstone materials should be viewed under artificial and natural light to check for color change. Then you can clearly label designs and customers can know they got "two designs in one" with a bold, color changing focal.

Interference is how the path of light through a stone is "interfered with" by the structure inside it. This gives rise to effects such as iridescence in labradorite and opal, chatoyancy in tigereye, schiller in sunstone and moonstone, among others.

Inclusions are any material trapped inside a gemstone while it is forming. These can include liquids, gasses, other minerals, even self-contained fractures. Inclusions can be tricky to evaluate: some indicate natural formation, some reveal human intervention, some lower the price of a gemstone—and others can make it priceless. The worth of a diamond decreases with inclusions, an emerald can be identified as natural by its inclusions and a piece of amber with a prehistoric insect inclusion can be priced at hundreds of thousands of dollars. Some forms of interference (above) come from inclusions, including aventurescence, opalescence, schiller, chatoyancy and more.

There are also significantly rarer optical phenomena, including asterism (most often found in corundums, spinel and diopside), tenebresence (most often found in spodumene, hackmanite and some zircons) and Usambara effect (most often found in tourmaline, epidote and corundum, each from specific sources).

Cleavage and Fracturing

Gemstones break in two ways; they can cleave or they can fracture, and in some cases, both can occur.

Gems that cleave tend to break along planes of weak atomic bonding. Atomic bonding refers to the attractive force that exists between atoms. They will typically break along lines that are parallel, perpendicular or diagonal to the crystal faces.

Gems that fracture tend to break along planes that have nothing to do with atomic bonds. Fractures are typically uneven, and each kind of fracture has its own descriptive name. Conchoidal (shell-like and scalloped in appearance) is the most common kind of fracturing found in gemstones.

It is important to remember that cleavage and fracturing are different than hardness. For instance, a diamond has the highest level of hardness, but it can still be damaged by a strong strike because it can be cleaved along its weak atomic bonds. And just like with hardness, cleavage and fracturing can influence how gemstones are cut, shaped and used in different forms of jewelry.

Emerald is a good example of the way cleavage can affect gemstone cut, shape and use. Even though emerald is a beryl, which is a 7-1/2 to 8 on the Mohs scale, this gemstone is highly prone to cleavage. So emeralds are faceted in ways that decrease the risk of chipping—that shape is even called "emerald cut" because it has been the most common shape for emeralds.

Natural cleavage is utilized in knapping—an ancient technique for shaping stone and volcanic glass.

Luster

When thinking about which gemstone to use in jewelry creations, optical properties such as color and luster carry a lot of weight.

Luster is determined by the way light reflects off the surface of the gemstone. The categories of luster are:

- Adamantine: Diamond

- Dull: Coral

- Greasy: Jadeite

- Metallic: Pyrite

- Pearly: Pearls

- Resinous: Amber

- Silky: Malachite

- Vitreous: Garnet

- Waxy: Turquoise

Luster can affect how a piece looks, so it is an important factor for designers to consider. If you are looking for a very shiny gemstone, vitreous gemstones such as garnet or amethyst would be a good choice. If instead you would like a raw organic look, possibly resinous amber or dull coral would be the most appropriate choice.

Gemstones are a staple in the jewelry-making industry, found all around the globe. A gemstone can be desired because of its natural appearance, scarcity or history with humans of note—adding color, light, meaning and value to designs.

Enhancement information, color, Mohs hardness, optical phenomena, cleavage, luster and metaphysical properties for individual gemstones can be found in each stone's Gem Note, an alphabetical listing for gemstone meanings and properties from amazonite to zoisite.

Since not all gemstones work in every type of jewelry application, designers will benefit from understanding gemological qualities such as luster, cleavage, phenomena and more to create designs that keep customers coming back for more.

Have a question regarding this project? Email Customer Service.

Copyright Permissions

All works of authorship (articles, videos, tutorials and other creative works) are from the Fire Mountain Gems and Beads® Collection, and permission to copy is granted for non-commercial educational purposes only. All other reproduction requires written permission. For more information, please email copyrightpermission@firemtn.com.